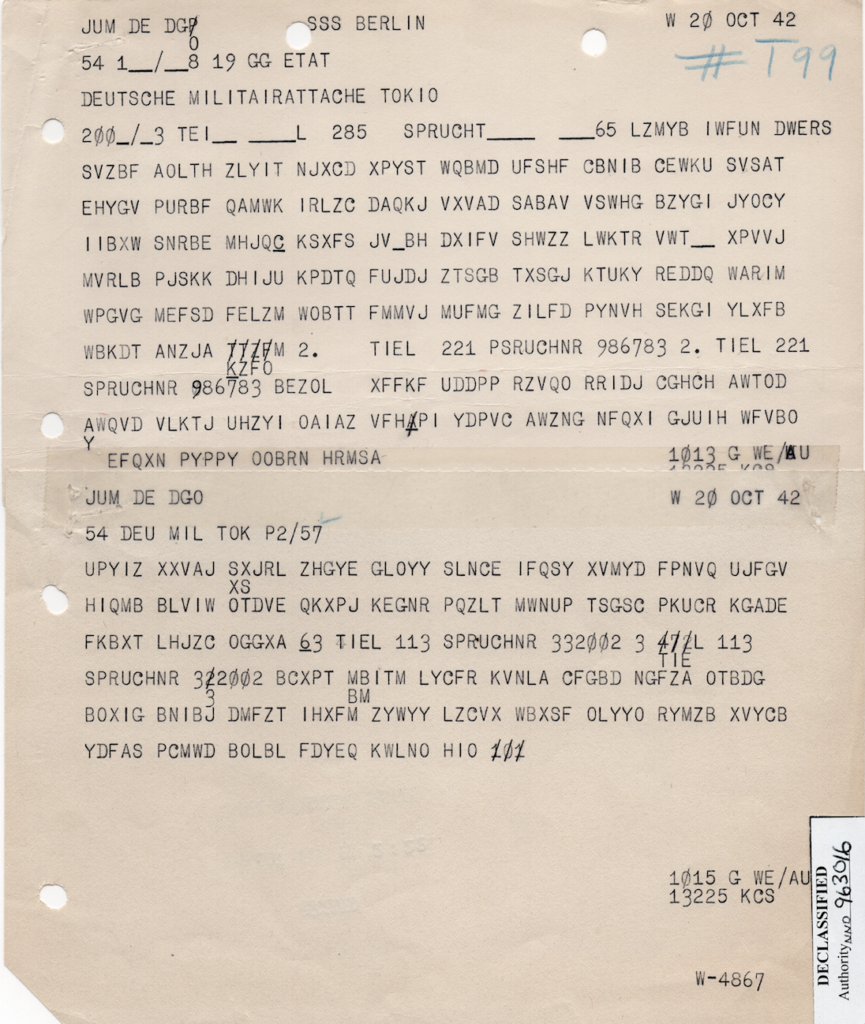

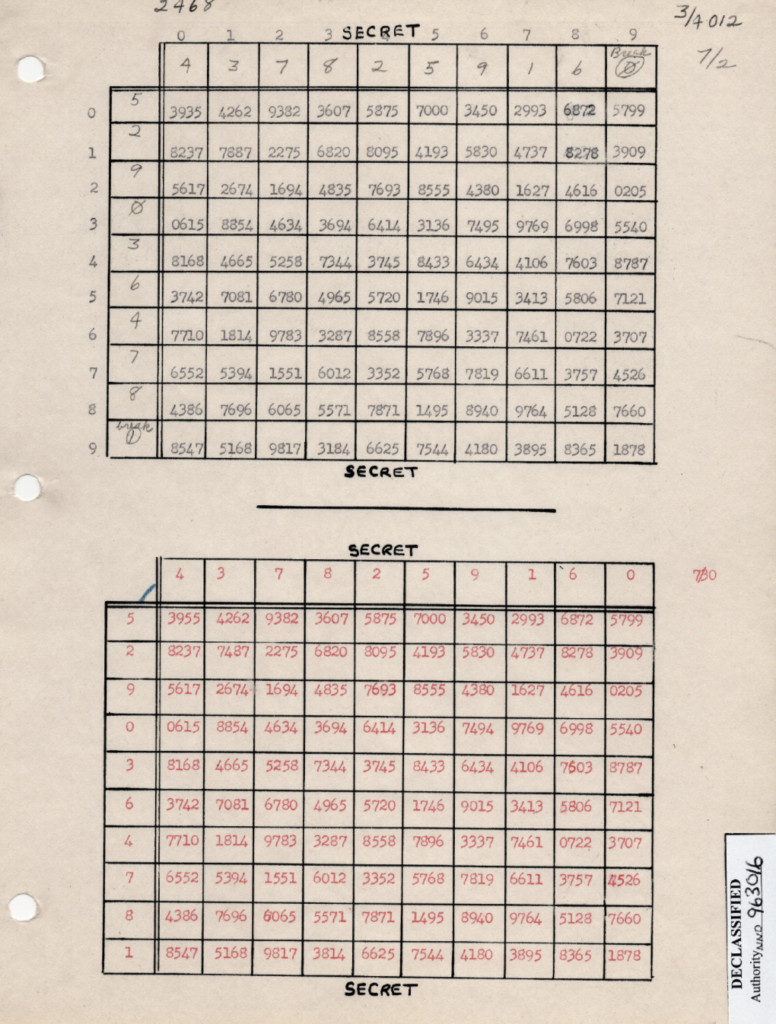

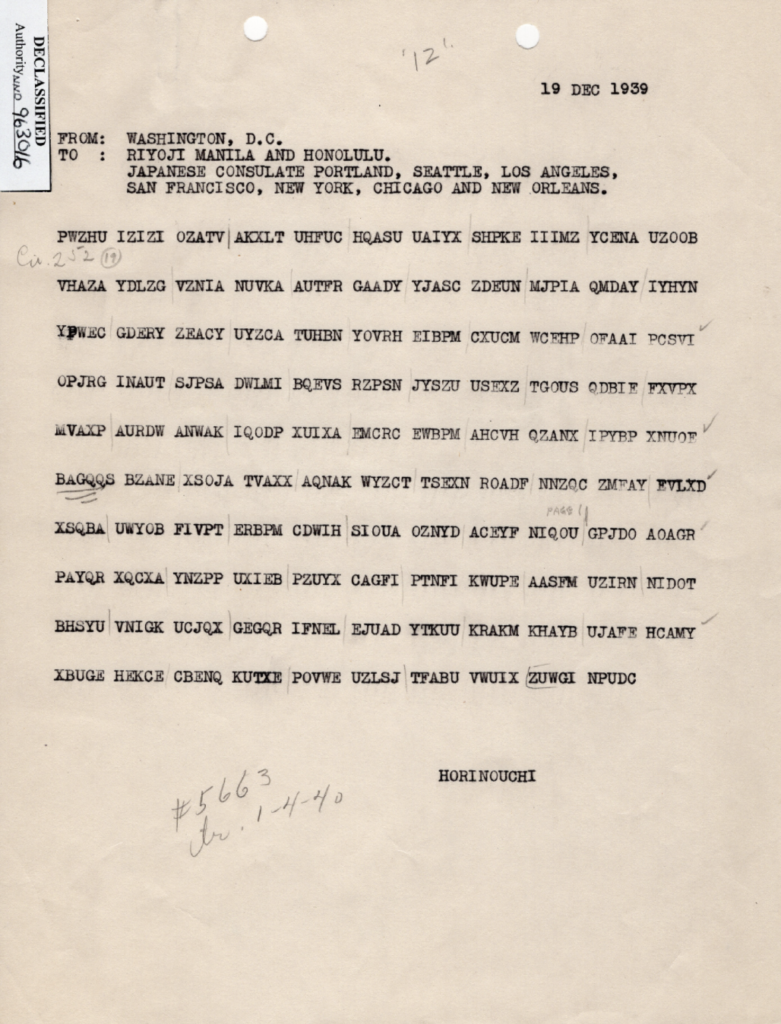

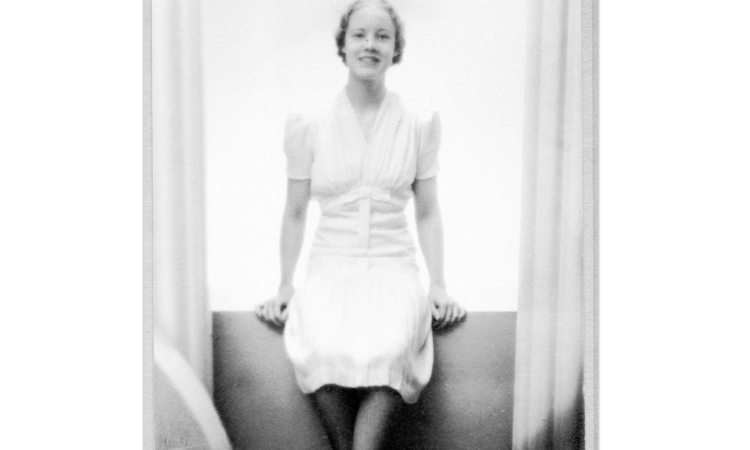

Genevieve Grotjan aspired to be a math professor but couldn’t find a university willing to hire a woman. In September 1940, after less than a year as a civilian Army code breaker, she made a key break that enabled the Allies to eavesdrop on Japanese diplomatic communications for the entirety of World War II. Courtesy of National Security Agency

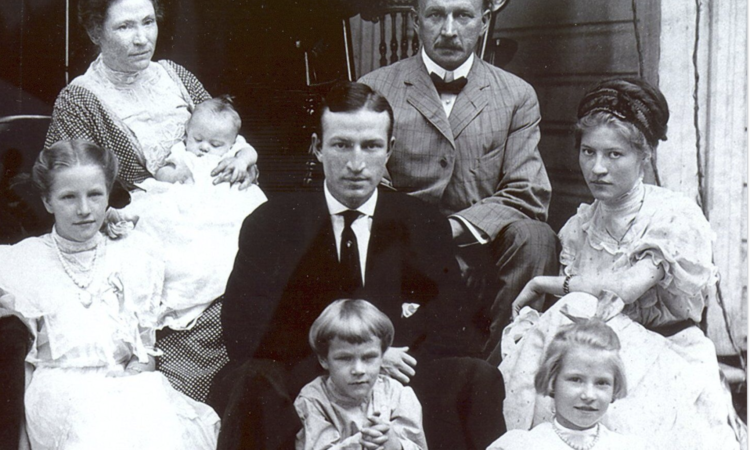

Genevieve Grotjan aspired to be a math professor but couldn’t find a university willing to hire a woman. In September 1940, after less than a year as a civilian Army code breaker, she made a key break that enabled the Allies to eavesdrop on Japanese diplomatic communications for the entirety of World War II. Courtesy of National Security Agency Agnes Meyer Driscoll (upper right), a former Texas high school math teacher, became one of the great cryptanalysts of all time, cracking Japanese Navy fleet codes during the 1920s and ’30s. Courtesy of National Security Agency

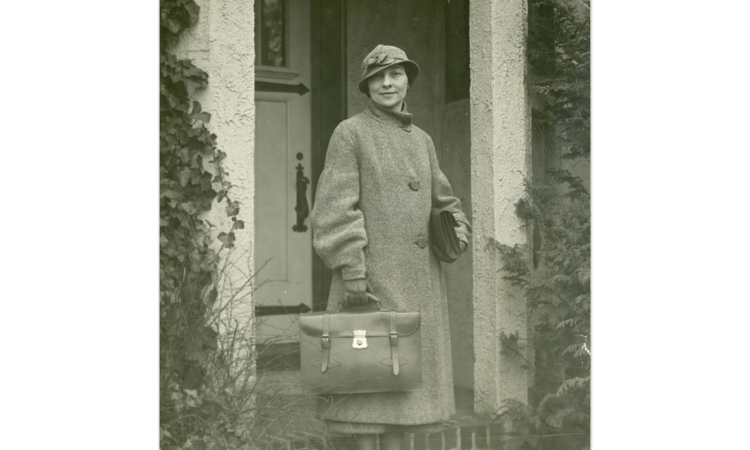

Agnes Meyer Driscoll (upper right), a former Texas high school math teacher, became one of the great cryptanalysts of all time, cracking Japanese Navy fleet codes during the 1920s and ’30s. Courtesy of National Security Agency Elizebeth Smith Friedman, another ex-schoolteacher, took a job in 1916 at an eccentric Illinois estate called Riverbank, where she helped found the U.S. government’s first codebreaking bureau. She later broke the codes of rumrunners during Prohibition. Courtesy of the George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, Virginia

Elizebeth Smith Friedman, another ex-schoolteacher, took a job in 1916 at an eccentric Illinois estate called Riverbank, where she helped found the U.S. government’s first codebreaking bureau. She later broke the codes of rumrunners during Prohibition. Courtesy of the George C. Marshall Foundation, Lexington, Virginia Women’s colleges in the 1940s were a mix of cerebral inquiry, marital ambition, and hallowed rituals. The 1942 May Court at Goucher College included Jacqueline Jenkins (fourth from left) and Gwynneth Gminder (second from right). Their lives changed when they received a secret summons from the U.S. Navy. Their classmate Fran Steen (next slide) also received one. Courtesy of Goucher College Archives

Women’s colleges in the 1940s were a mix of cerebral inquiry, marital ambition, and hallowed rituals. The 1942 May Court at Goucher College included Jacqueline Jenkins (fourth from left) and Gwynneth Gminder (second from right). Their lives changed when they received a secret summons from the U.S. Navy. Their classmate Fran Steen (next slide) also received one. Courtesy of Goucher College Archives

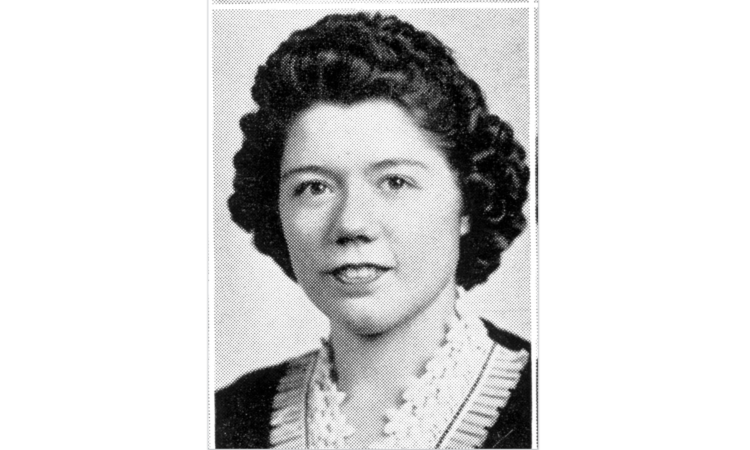

Dorothy Ramale, shown here in her 1943 yearbook photo, grew up on a farm in Pennsylvania and wanted to be a math teacher. But the dean of women at Indiana State Teachers College called her in and told her the U.S. Army had another idea for her. Courtesy of Indiana University of Pennsylvania Special Collections

Dorothy Ramale, shown here in her 1943 yearbook photo, grew up on a farm in Pennsylvania and wanted to be a math teacher. But the dean of women at Indiana State Teachers College called her in and told her the U.S. Army had another idea for her. Courtesy of Indiana University of Pennsylvania Special Collections The U.S. Navy took possession of Mount Vernon Seminary, a girls’ school in tony upper northwest Washington, D.C., adding hastily erected barracks to house four thousand female code breakers. Courtesy of D.C. Department of Transportation

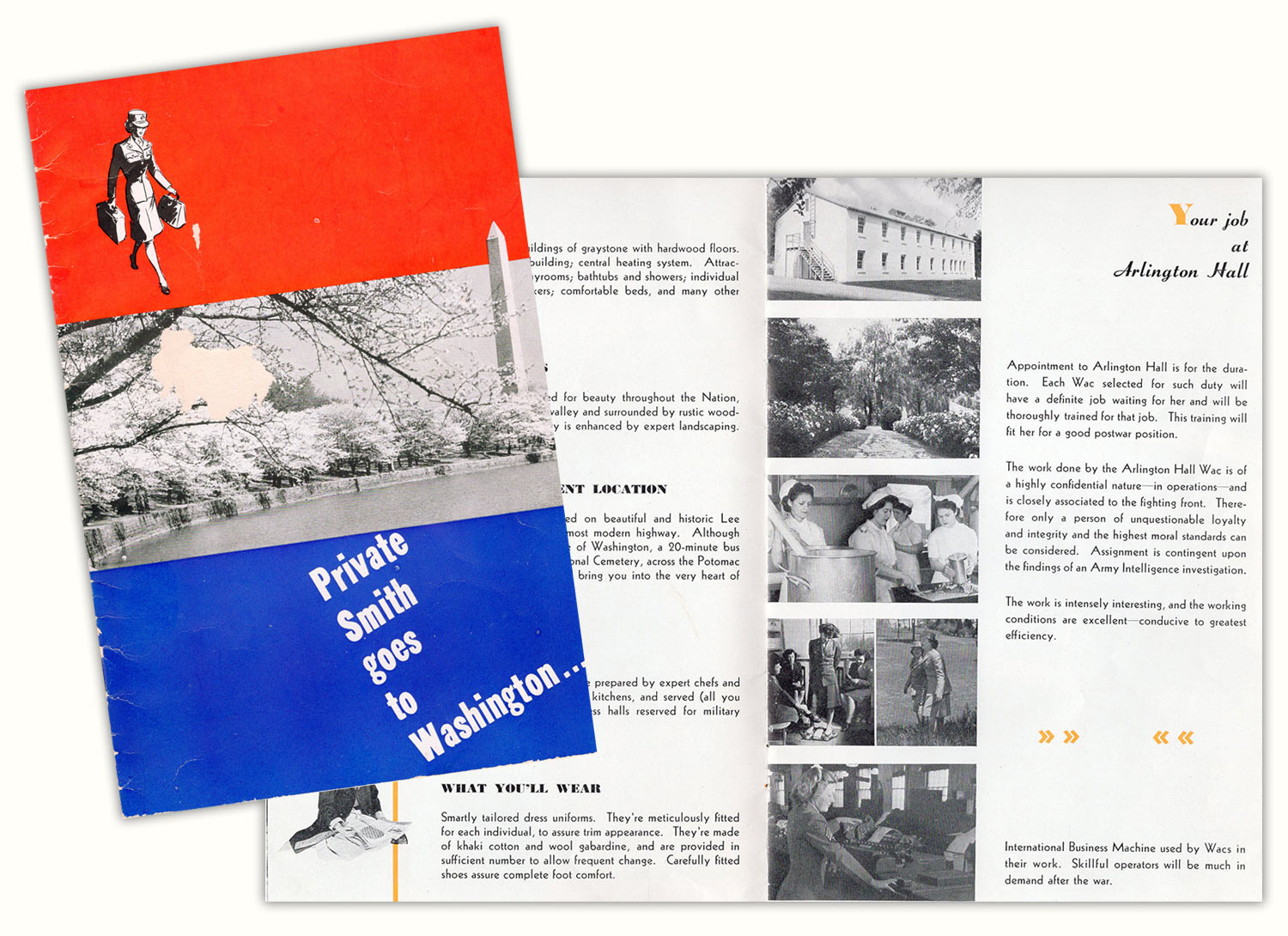

The U.S. Navy took possession of Mount Vernon Seminary, a girls’ school in tony upper northwest Washington, D.C., adding hastily erected barracks to house four thousand female code breakers. Courtesy of D.C. Department of Transportation Many rented tiny rooms at Arlington Farms, a Virginia dormitory built to house seven thousand women workers, known as government girls or g-girls, for the war’s duration. Locals dubbed it “Twenty-Eight Acres of Girls.” Government photographer Esther Bubley documented their lives.

Many rented tiny rooms at Arlington Farms, a Virginia dormitory built to house seven thousand women workers, known as government girls or g-girls, for the war’s duration. Locals dubbed it “Twenty-Eight Acres of Girls.” Government photographer Esther Bubley documented their lives. When, in the spring of 1943, a group of members of the WAVES were loaded onto a troop train and sent “west” under sealed orders, they hoped they might be headed to California. They emerged to find they were in Dayton, Ohio on a secret, unknown, but highly urgent mission. From the collections of Dayton History

When, in the spring of 1943, a group of members of the WAVES were loaded onto a troop train and sent “west” under sealed orders, they hoped they might be headed to California. They emerged to find they were in Dayton, Ohio on a secret, unknown, but highly urgent mission. From the collections of Dayton History At Arlington Hall, Ann Caracristi (far right), an English major from Russell Sage College, matched wits against Japanese code makers, solving message addresses and enabling military intelligence to develop “order of battle” showing the location of Japanese troops. The messages would then be passed along to Dot Braden and other women whose efforts led to the sinking of Japanese ships. Courtesy of National Security Agency

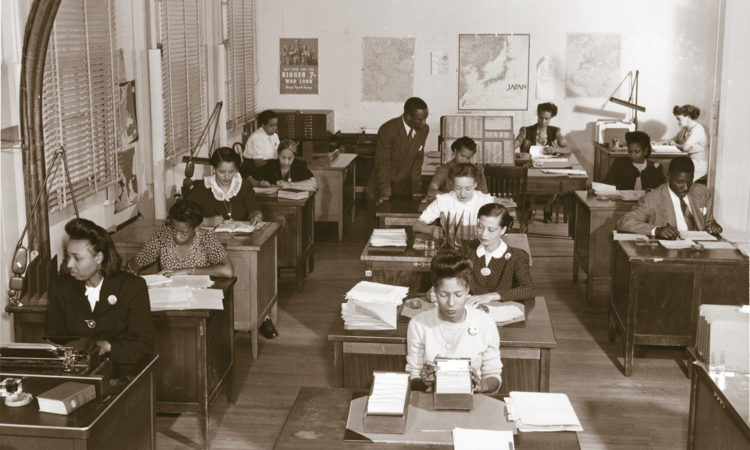

At Arlington Hall, Ann Caracristi (far right), an English major from Russell Sage College, matched wits against Japanese code makers, solving message addresses and enabling military intelligence to develop “order of battle” showing the location of Japanese troops. The messages would then be passed along to Dot Braden and other women whose efforts led to the sinking of Japanese ships. Courtesy of National Security Agency Also at Arlington Hall, a secret African American unit—mostly female, and unknown to many white workers—tackled commercial codes, keeping tabs on which companies were doing business with Hitler or Mitsubishi. Courtesy of National Security Agency

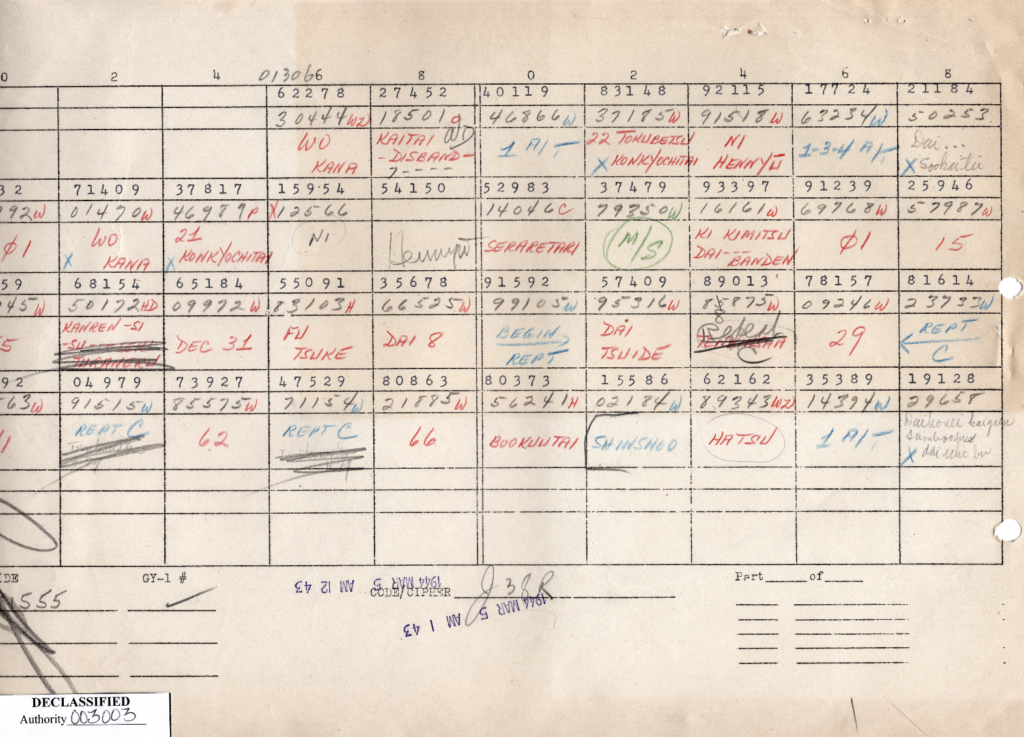

Also at Arlington Hall, a secret African American unit—mostly female, and unknown to many white workers—tackled commercial codes, keeping tabs on which companies were doing business with Hitler or Mitsubishi. Courtesy of National Security Agency The Navy women broke enemy naval codes used across the world’s major oceans. Women formed the cryptanalytic assembly line that exploited the Japanese fleet code known as JN-25. They helped in the effort to shoot down the plane of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of the attack at Pearl Harbor. “We really felt we had done something really fantastic,” said one, Myrtle Otto. “That was an exciting day.” Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration

The Navy women broke enemy naval codes used across the world’s major oceans. Women formed the cryptanalytic assembly line that exploited the Japanese fleet code known as JN-25. They helped in the effort to shoot down the plane of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of the attack at Pearl Harbor. “We really felt we had done something really fantastic,” said one, Myrtle Otto. “That was an exciting day.” Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration During their off hours, the women wrote letters incessantly, sending the missives—often with an enclosed snapshot—to soldiers and sailors. One g-girl was writing twelve different men. Courtesy of Library of Congress

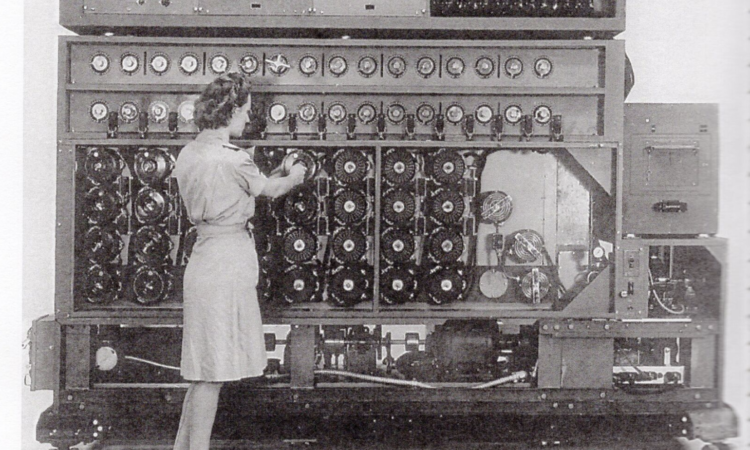

During their off hours, the women wrote letters incessantly, sending the missives—often with an enclosed snapshot—to soldiers and sailors. One g-girl was writing twelve different men. Courtesy of Library of Congress Women also ran the machines that attacked the German Enigma ciphers, maintained wall maps that kept track of U-boat locations and Allied convoys, and wrote intelligence reports that would be used by naval commanders. Courtesy of National Security Agency

Women also ran the machines that attacked the German Enigma ciphers, maintained wall maps that kept track of U-boat locations and Allied convoys, and wrote intelligence reports that would be used by naval commanders. Courtesy of National Security Agency On their rare days off, the women would ride buses and streetcars to the beaches of Virginia and Maryland. This group of Arlington Hall code breakers includes Crow (far left), and Dot (peeking out from behind the pole). Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce

On their rare days off, the women would ride buses and streetcars to the beaches of Virginia and Maryland. This group of Arlington Hall code breakers includes Crow (far left), and Dot (peeking out from behind the pole). Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce Many women stayed friends for decades after their service. A group of Navy women kept a “roundrobin” letter going for seventy-five years. The group included Elizabeth Allen Butler (front far left), Ruth Schoen Mirsky (front, second from right), and Georgia O’Connor Ludington (back, second from right). Courtesy of Ruth Mirsky

Many women stayed friends for decades after their service. A group of Navy women kept a “roundrobin” letter going for seventy-five years. The group included Elizabeth Allen Butler (front far left), Ruth Schoen Mirsky (front, second from right), and Georgia O’Connor Ludington (back, second from right). Courtesy of Ruth Mirsky Dot and Crow’s friendship remained so strong that Crow insisted Dot and her husband, Jim Bruce, come to Washington to meet her own fiancé, Bill Cable, and give their stamp of approval before she would marry him. Jim Bruce is at right and Bill Cable is at left. Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce

Dot and Crow’s friendship remained so strong that Crow insisted Dot and her husband, Jim Bruce, come to Washington to meet her own fiancé, Bill Cable, and give their stamp of approval before she would marry him. Jim Bruce is at right and Bill Cable is at left. Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce The women took their oath of secrecy so seriously that even now, at age ninety-seven, Dorothy Braden Bruce (shown here at her birthday party with her grandchildren) has trouble bringing herself to utter certain words she was told never to say outside the grounds of Arlington Hall. Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce

The women took their oath of secrecy so seriously that even now, at age ninety-seven, Dorothy Braden Bruce (shown here at her birthday party with her grandchildren) has trouble bringing herself to utter certain words she was told never to say outside the grounds of Arlington Hall. Courtesy of Dorothy Braden Bruce